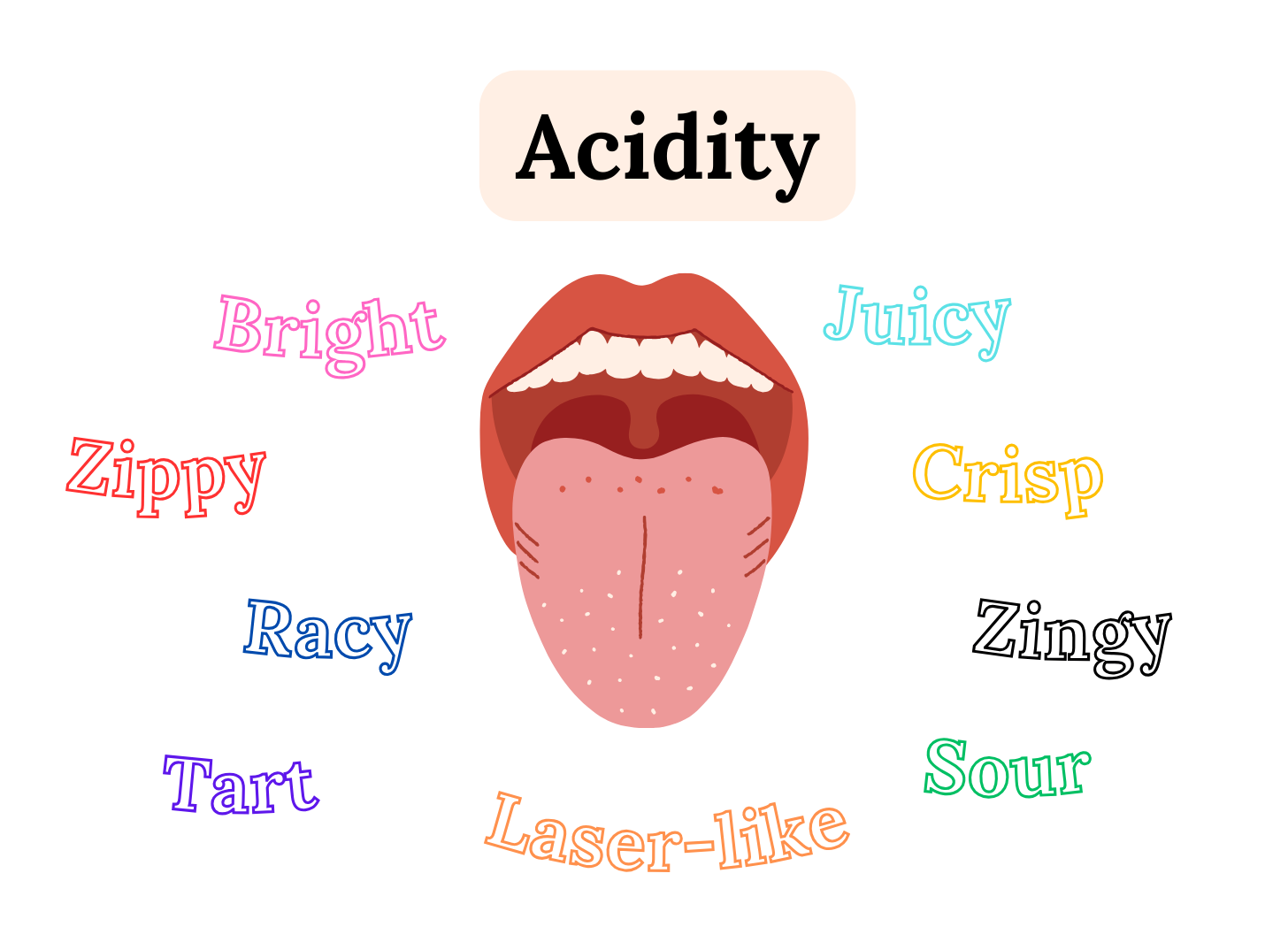

Structure Deep Dive: Acidity in Wine

Today, our tour through the components of a wine’s structure continues! Last month, we wrote a post on tannins, and today we’re exploring the acidic sub-7 side of the pH scale. As always, this landscape is full of rabbit holes (mainly of the organic chemistry variety), but despite the title, we plan to keep the info, dare we say, basic? Puns aside, let’s get into it.

The Big Picture

Acidity is one of the main pillars of a wine’s structure and greatly affects our perception of the wine (as well as how a wine ages, but we won’t get into that today). All wines are acidic, sometimes to a degree that really makes your mouth water, and other times where the acid hardly feels present at all. A wine with higher acid will feel lighter and fresher on the palate, whereas a wine with lower acidity will feel softer and rounder*.

Ideally the acidity in a wine is in what’s called “in balance”—meaning that the acidity is working together harmoniously with all the other parts of the wine and thus isn’t too high or too low to be stirring up trouble. Think of lemonade—it has a lot of acid from the lemon juice, but also a lot of sugar, which results in a bright, refreshing drink. If a lemonade was just sugar water with lemon flavor, it would be way too cloying, one-dimensional, and, what we call in the wine world, “flabby”—the official term for a wine that is too low in acid to be in balance. Or, if there was way too much acid for the amount of sugar, it would be tart, sour, etc. Depending on its alcohol content, sweetness, tannin level, and fruit concentration, the wine will have different amounts, and types, of acid.

Know Thyself

But, when it comes to acid, there isn’t just one sweet spot (so to speak) for everyone, because we all have different tolerances for acidity. So even though a wine might technically be balanced in its acid, it may taste too acidic or too flabby for you. As mentioned in the inaugural Sauvignon Blanc post, Erica is a proud “acid hound”, while Jaime has a lower tolerance for acid, and this affects what wines we like. It’s important to know your own palate, so you can navigate your way to the wines you like, and better communicate this when you’re out at a restaurant or a wine shop. You may already know your preference—do you like Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Grigio, and other bright, zippy wines? Or do you prefer a big smooth Chardonnay? This may indicate which end of the spectrum you tend towards.

High Acid is Not the Same Thing as Dry!

One small note—high and low acidity is not an indicator of the dryness of a wine, although it is often incorrectly used as such. In the wine world, a dry wine is a wine with no residual sugar—that’s it. It doesn’t tell you anything else about the wine. Dry wines can be super zippy (high acid), but they can also be fruity and/or oaky with lower acid, which makes them softer and full and may make them seem sweet, even though they’re not. Most wines that we consume are dry wines, and we usually specify if they’re not, calling them dessert wines, or off-dry.

Sweetness refers to how much sugar is in the wine, and is not a measure of fruitiness or acidity. In fact, sweet wines are necessarily high-acid wines, because otherwise they would be overwhelmingly cloying (think of the lemonade example above). So, when you’re out in the world, we recommend staying away from describing a wine you want as “dry”, because it’s imprecise. Instead, talk about acid level, and see where it takes you.

What affects the acid in a wine?

Many things: the variety of grape, the ripeness of the grape, and the winemaking. Let’s start with the grape—some grapes reliably are at one spectrum or the other (more on this below). But many grapes are chameleons—they can be higher or lower in acid, depending on the other factors listed. Chardonnay is in this camp: even though most people associate it with a smoother rounder wine, it can also be quite zippy, depending on the region and the winemaking.

The ripeness of the grape also affects acid, because fruits are more acidic when they’re unripe (think of an unripe peach), and then lose acid as they become more ripe (think of a ripe peach). Cooler climates lead to grapes that are less ripe, and thus more on the acidic end, while warmer climates lead to riper grapes with less acid (generally), but you can also harvest the grapes early in a warmer climate to maintain that same acidity.

Finally, there’s the winemaking. Winemakers can acidify a wine—add acid back into the grape must before fermentation, but it’s generally frowned upon in the world of fine wine, so we won’t go into that avenue here. Instead, we’ll focus on malolactic fermentation, a process that changes the acids in the wine to great effect.

Malolactic Fermentation

Tartaric, malic and citric acid are the most common forms of acid found in wine. Malolactic Fermentation (MLF) is also known as malolactic conversion**, and it’s a conversion of malic acid into a fourth acid: lactic acid. These come from the Latin roots “mālum” for apple, and “lac” for milk. Malic acid is harsher than lactic acid (think of a green apple versus yogurt), so if a wine undergoes “malo” or MLF, it will feel softer and less acidic on the palate. This is one way that a winemaker can affect a wine’s acidity. If a wine is too high or harsh in acid, they may have it undergo MLF so it becomes softer. Or, if a wine is already at desired acid level, they may block MLF from occurring. But MLF, too, is a spectrum, and a winemaker can choose to make a wine where only some of the acid has undergone MLF, so you may see something out there like 20% MLF.

In addition to changing the acid, MLF stabilizes the wine and also changes the aromas. Most notably, one by-product of MLF is the molecule diacetyl, which is the aroma most associated with butter. This is where your classic 90s California Chardonnay got its “buttery” moniker, these wines would usually undergo “full malo” and thus have a pronounced buttery aroma. These over-the-top wines may have given MLF a bad rap, but don’t let that have you discount it all together! Careful and thoughtful winemaking can seamlessly integrate MLF so it enhances, rather than detracts, from the wine.

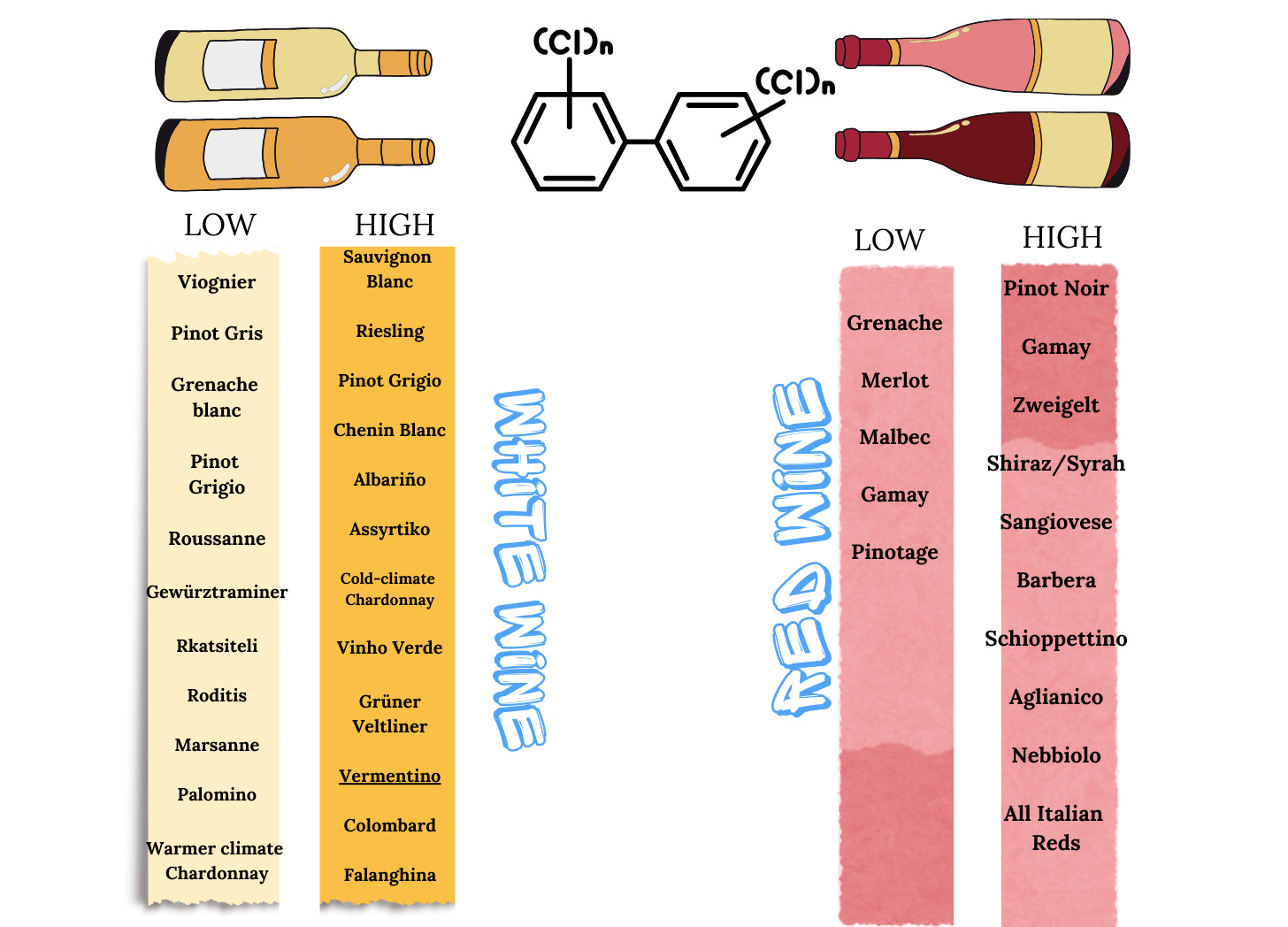

Classically Higher Acid Wines

As mentioned above in the “What affects the acid in a wine?” section, some grape varieties are reliably higher acid, while others can be higher or lower, depending on the climate and winemaking. We have listed a few reliably high acid wines here. Sparkling wines are also high-acid wines.

Higher-Acid White Wines and Varieties

Riesling

Pinot Grigio

Chenin Blanc

Albariño

Assyrtiko

Grüner Veltliner

Colombard

Falanghina

Cold-climate Chardonnay (e.g. Chablis, Finger Lakes, Oregon)

Vinho Verde

White Bordeaux

Higher-Acid Red Wines and Varieties

Pinot Noir

Gamay

Zweigelt

Syrah

Sangiovese

Barbera

Schioppettino

Aglianico

Nebbiolo

Honestly, most of the Italian reds will be here

Classically Lower Acid Wines

These tend to be lower in acid, but again, it can vary by region and winemaker. In addition, sherry and sake would also belong in this camp.

Lower-Acid White Wines and Varieties

Gewürztraminer

Viognier

Pinot Gris

Grenache blanc

Roussanne

Marsanne

Palomino

Warmer climate Chardonnay (California***, Australia, etc.)

Lower-Acid Red Wines and Varieties

Grenache

Merlot

Malbec

Pinotage

We hope this helps you navigate where you fall in your own preference for acidity in wines. Until next time, may you drink well!

Fun Fact

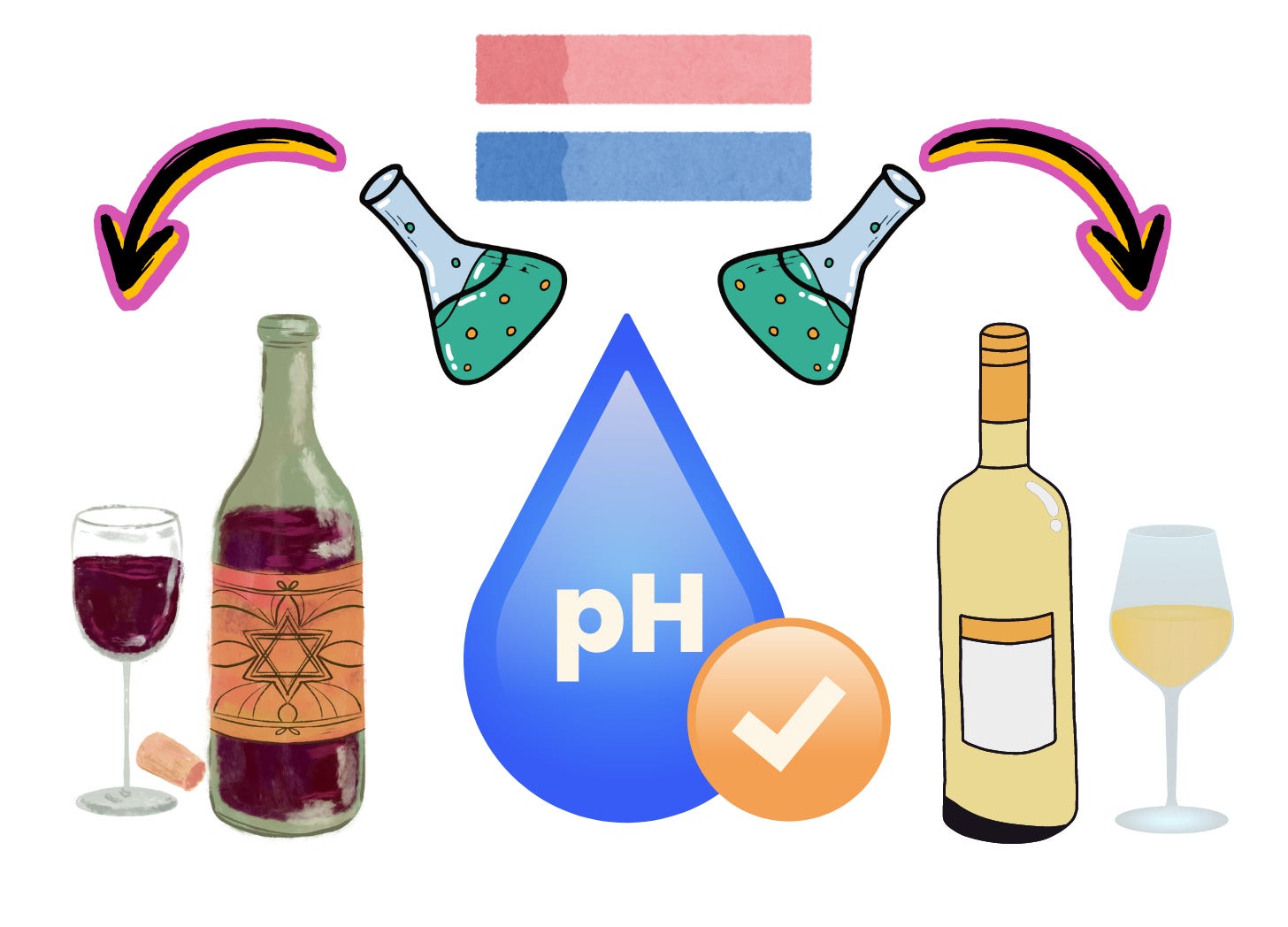

Because the pH affects the anthocyanin pigments in the wine, the acidity will also affect a wine’s color. Lower acidity wines tend to have more blue/purple tones, and higher acidity leading to redder tones.

*Wines usually fall between 2.9 to 4.2 on the pH scale, though in practice, most winemakers aim for a pH of 3 to 3.5 (remember that higher acidity means a lower pH). You don’t really need to know this unless you like to get into the nitty gritty. Winemakers will often publish the pH of the wine as part of the tech sheet—these are basically the specs of a wine that the winemaker makes available so that people can read in detail how the wine was made.

**One by-product of this process is CO2, which gives the appearance of a fermentation, (even though it’s not) thus the name.

***California needs a caveat, as it’s a very big place with a vast array of wines, and includes both warm and cool growing regions. The California-style of Chardonnay tend to be lower in acid, but there are many, many talented winemakers growing Chardonnay in cool-climate areas that are much zippier than the traditional California style. Similarly Australia, though overall a warm place, has cool climate growing areas as well.